Learn Kanji Radicals

About the Project

(This is a sister project to Learn Kanji Sound Components, therefore the copy here will be similar.)

This is a simple app that assists in helping learn how to infer the meaning of Japanese Kanji characters from their parts.

I have been learning Japanese on my own for over five years.

Japanese uses two types of scripts, kana and kanji.

Kanji were brought to Japan from China over a thousand years ago by immigrants.

At this time, Japanese was only a verbal language, it did not have a writing system of its own.

The Japanese writing system began by taking existing Chinese characters, preserving their original Chinese meaning and attaching the Japanese pronunciation of these concepts.

There are thousands of kanji that are currently in use, and most kanji have multiple valid pronunciations.

Happily, the original Chinese characters had an inbuilt system that made it easier to infer the meaning and pronunciation of a kanji by looking at it.

Basically, they are made up of components, these components hold information about the meaning and pronunciation about the kanji.

The parts that have meanings associated with them are called 部首 (bushuu) or in english; Radicals.

By committing to memory what these radicals mean, it’s possible to infer the meaning of a lot of kanji - even in the case where you are unfamiliar with said kanji.

Here is a simple example:

木

This is both a kanji and a radical, it means “tree”

森

This is the Kanji for “forest”. Notice how it’s made up of three trees.

Here is another:

人

This is both a kanji and a radical, it means “person”

休

This is the Kanji for “rest”. Notice how there’s a person by a tree. Now imagine them relaxing there.

If you are interested in the specifics of how this works, please read this article.

How it is used

The app is very straightforward.

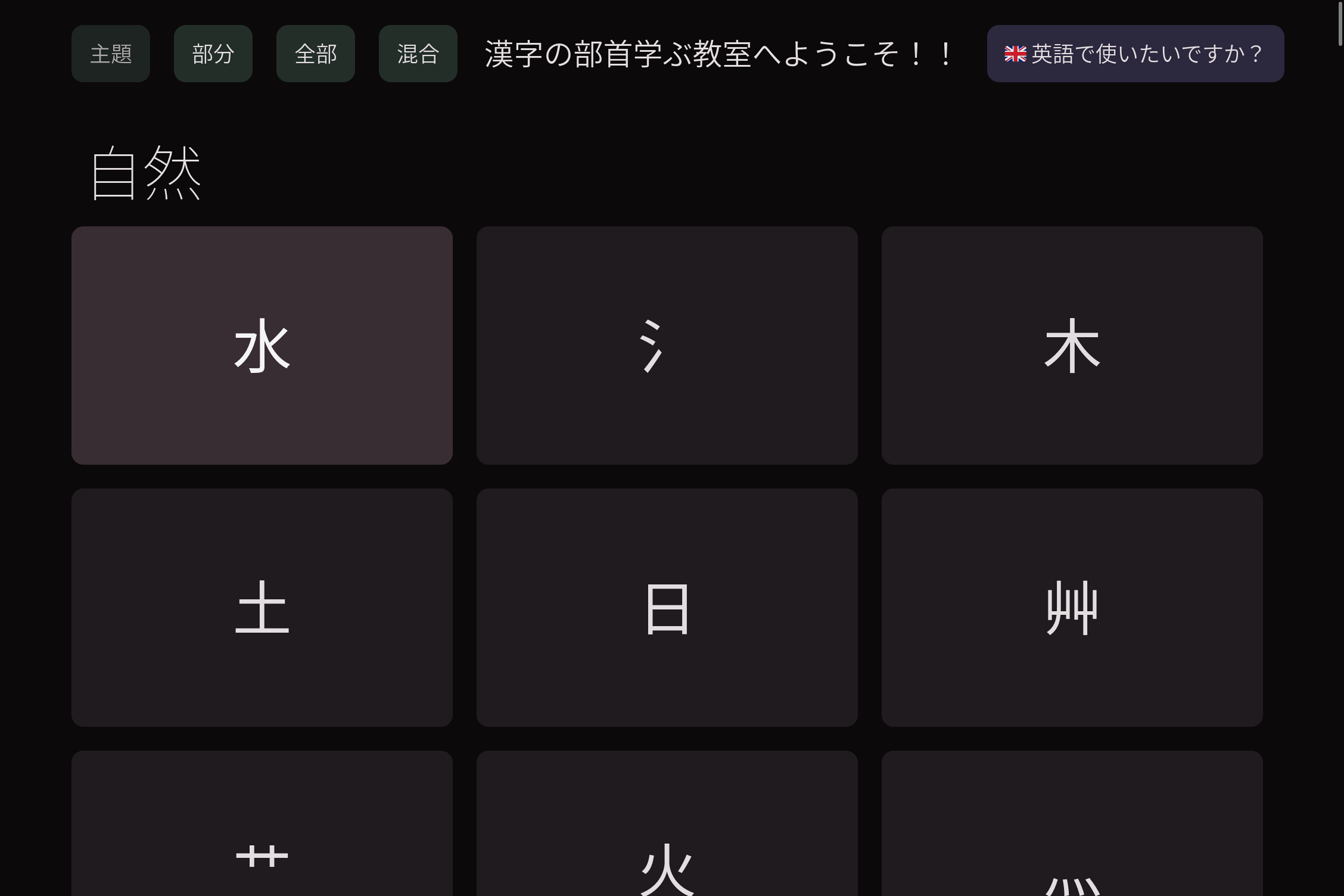

Basically there is a grid of flashcards each with a “radical”, and you can click on one to see:

- The name of the radical

- The meaning of the radical

- Which part of the kanji it tends to appear in (eg; left, right, top, bottom, middle)

By default, they are all grouped into conceptual categories.

These are:

- Nature

- Body Parts

- People

- Enclosures

- Verbs and Language

- Natural Materials

- Maths and Measurement

- Food

- Animals

- Warfare

- Man-made Tools

- Senses

- Supernatural

There are buttons on the top left that:

- Change the categories from conceptual categories to grouping the radicals by which position they tend to appear in Kanji (top, bottom, left, right, etc)

- Turn off categories altogether

- Shuffle the order of all the radicals

The idea here is that it’s more efficient to learn radicals with a similar meaning together, but it is more meaningful to test yourself without categories or a consistent order.

There is a button in the top right that changes the language of all text used towards the app, between English and Japanese.

When learning a language there is a point where it is good practice to switch all of your devices to said language and basically do anything you can in it, get any exposure you are able.

How it was built

Learn Kanji Radicals was written in Elm, a functional, strictly-typed, ML-inspired language that compiles to Javascript.

It’s tagline is “A delightful language for reliable web applications” which I definitely agree with.

The idea of a functional language, is basically that an app is written as a large collection of functions which simply take an input and modify an output with no side effects.

Building software in this way makes it much easier to parse, read and maintain over the long term.

My experience using functional languages like Elm has definitely improved my ability to write clean, maintainable code even when using other languages.

Elm here replaced both the HTML and the Javascript, and I used the package Elm UI to style the app, effectively replacing CSS.

Instead of three different languages, and potentially one or more Javascript frameworks, the whole app was written in Elm.

The only thing I don’t like about Elm is that when it compiles to HTML, CSS and Javascript, the resultant code is illegible.

If you were to view the source from the browser, the result would be difficult to read and make sense of. The names of variables, functions, classes and so forth would not be meaningful as they were generated at compile time.